- U.S. Postal System

The Second Continental Congress and the U.S. Postal System

The U.S. postal system lends much of its organization and operations to the first postmaster general, Benjamin Franklin. Already well-known for his work as joint deputy postmaster general in British North America, Franklin would bring innovation to the way information was disseminated across the country.

Click the image to expand

Fairbanks Tavern: The First Post Office

Prior to Franklin's development of the continental post office, sending a written message to another person required either having a relative, friend, servant, or enslaved person make the journey for you or paying someone to hand-deliver the message.

Sending written messages was not needed much, partly because writing a letter required you to be literate, which was limited to those wealthy enough to be educated. In addition, most of the people an average person would need to talk to would already be within traveling distance, so you could just go see them rather than sending a message. For this reason, the colonies didn't need a postal service until they grew much larger. However, some people did need to send messages, such as businessmen and politicians who had to communicate with their superiors or colleagues back in Europe. To send a message, they would have to pay a merchant to take the message across the ocean, which ship captains would do for a fee.

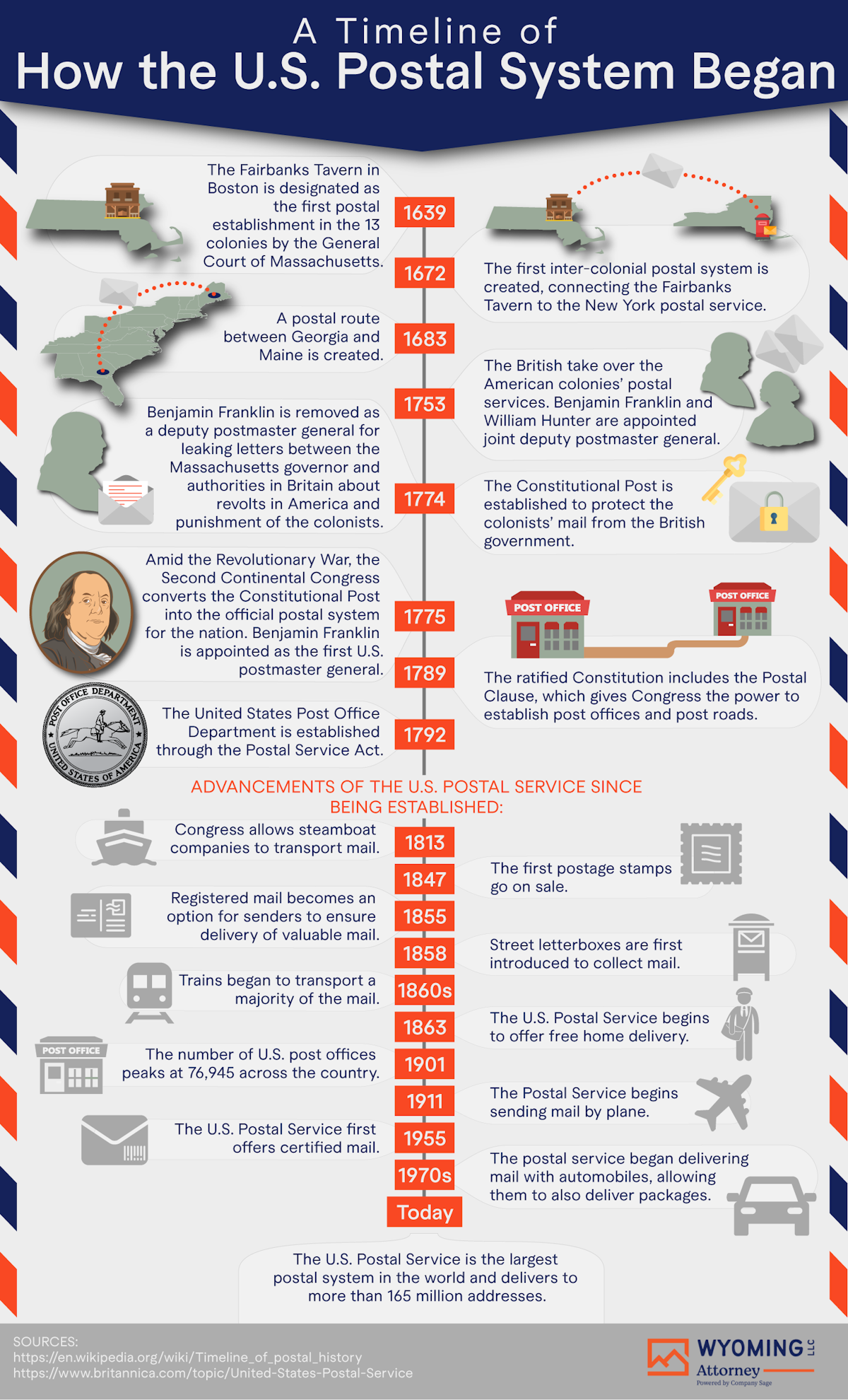

As the need for communication with the Old World increased, it became necessary to set up a place to hold these messages until a merchant could take them on their next journey. Meanwhile, mail also came to North America, and someone was required to sort and deliver these messages. Thus, Fairbanks Tavern in Boston, Massachusetts, became the first official post office for the colonies. In 1639, the Massachusetts General Court gave Richard Fairbanks, owner of the Fairbanks Tavern, charge of all mail that came in through Boston. Fairbanks's responsibility was to deliver every letter, and he was paid per piece of mail.

By 1672, the first postal route in the continental post services was established, connecting Fairbanks Tavern in Boston with the postal service in New York to create the first intercolonial postal system. In 1683, a postal route was laid out between Georgia and Maine. Many attempts to create a single intercolonial mail service for all 13 colonies were made, but none were successful until the appointment of Franklin.

In 1753, the British crown took control of the postal services for the American colonies. Franklin was appointed as joint deputy postmaster general along with a man named William Hunter. During Franklin's term, he traveled around 1,600 miles throughout the colonies. Franklin designed an odometer to measure the distance his carriage traveled, and he used the information he gathered to create the most efficient routes for mail carriers. He also changed the rates for transporting mail to be based on weight and distance traveled. In addition, he mandated distribution of newspapers, which improved the dissemination of information throughout the colonies. The changes Franklin implemented resulted in both quicker delivery of mail and a profit for the post office.

Benjamin Franklin and the Hutchinson Affair

In December 1772, Franklin was in London for business, serving as an agent of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. While there, he received a parcel containing letters from an anonymous sender. The letters were intercepted correspondence between Massachusetts Gov. Thomas Hutchinson, Lt. Gov. Andrew Oliver, and authorities in Britain. The letters discussed the revolts happening in the North American colonies and requested reinforcements and permission to impose harsher treatment of the colonists.

Franklin, who stood with the colonists, forwarded these letters to the Massachusetts House of Representatives with explicit instruction to discuss them only in committee and not publish them. Despite his instruction, the letters were leaked and published in the Boston Gazette in June 1773. The result was civil unrest and eventually the Boston Tea Party in December 1773.

As suspicion of who had released the letters to the public began to spread, Franklin took action and wrote a letter published in the London Chronicle claiming responsibility, in part, for the letters. As a result of these actions, Franklin was removed from his position in 1774.

What Did the Second Continental Congress Do?

After Franklin's dismissal, the colonies were put under more scrutiny. The British government authorized its postal workers to open and read correspondence between colonists. With tensions rising to the point of war, the colonists formed their own postal service. William Goddard, a fellow postmaster and printer, established the Constitutional Post. Its mail carriers had to be highly regarded and carried the mail under lock and key, working as guards as well as delivering the mail. By the end of 1775, there were 30 post offices operating as part of the Constitutional Post.

So what did the Second Continental Congress do? It set the stage for change. Shortly after the start of the Revolutionary War, the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia in May 1775, and what happened at the Second Continental Congress set the stage for the American postal system of today. The war brought new concerns in terms of correspondence and security, and due to the nature of the highly trusted postal workers in the continental post services, it was agreed that the Constitutional Post would be converted into the official postal system of the new nation, with Franklin as the postmaster general. To assist with the passing of military information from Congress to the Continental Army, the mail carriers were made exempt from military service.

Communication and Innovation

Following in the footsteps of Franklin, the United States Postal Service continued to innovate after the Revolution to ensure that the mail could be delivered more quickly and efficiently. For instance, postal workers were originally on horseback, traveling along approximately 2,400 miles of road created by the United States government. But as settlement moved westward, the postal system began to use stagecoaches.

In 1813, just six years after the launch of commercial steamboats, Congress permitted contracts with steamboat companies to transport the mail. By 1848, mail was being transported by steamboat to California via the Isthmus of Panama.

After the Civil War, the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad allowed for mail to be sorted and transported across the United States. Train services would handle up to 93% of non-local mail sent in the United States from the 1860s to the 1970s. With the rise of the automotive industry and the movement of the population into cities, the postal service began using automobiles. This also gave carriers the ability to carry packages in addition to letters.

As technology continued to evolve, the postal service began to send mail via planes in 1911. This allowed for mail to be delivered across continents in the shortest period of time. In 1924, the first transcontinental delivery of mail by air took one day, ten hours, and 20 minutes. Today, the same flight only takes six to seven hours.

The modern postal system continues to innovate, using automated sorting services and other types of technology to improve the way mail is delivered. Today, the United States Postal Service is the largest postal system in the world, delivering to more than 165 million addresses across the country and its territories.

- British Post Office (Revenues) Act of 1710

- Mail Service in the Colonial Era

- Hugh Finlay and the Postal System in Colonial America

- Benjamin Franklin, Postmaster General

- United States Postal Service

- Privacy and Anonymity in Business

- Letters of the Revolutionary War

- Transportation in America's Postal System

- The Great Link Between Minds: The United States Postal Service

- Spy Techniques of the Revolutionary War

- History of the United States Postal Inspection Service

- How the U.S. Post Office Has Delivered the Mail Through the Decades

- Constitution Annotated: Power to Protect the Mail

- Registered Agents to Handle Your Mail

- Establishing the Postal Service

- United States Postal Service Quick Facts